I lie in the fells, on the northern side of Sána (Saana). Beneath my hands, I feel the tundra’s low growth, its roughness, and the movement caused by the wind in it. At night, I lie in my bed in Kiekula. Yet in my body, it is as if I still rest among the fells. I am in a place unknown to me, a landscape new to my eyes. Here, in Sápmi, I am a guest.

Rusokääpä (Pycnoporellus fulgens) rya is part of the Siimes – katve -series. Photo: Ida Lindgren.

I applied to the Bioart Society’s residency at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station with the intention of studying regionally endangered lichens, their growth, colours, forms, and environments. My aim was to weave a rya for my upcoming solo exhibition based on these observations. I am currently preparing the second part of the Siimes – katve series, to be shown at Galleria Centrum in Karjaa from 2 September to 29 November 2025.

Siimes – katve II continues a series whose growing collection of ryas, each tied slowly by hand, reflects the undisturbed and patient conditions that endangered species require, and the fragile increase in their occurrences when such conditions exist. The ryas embody different species, while also bringing the presence of their sustaining habitats into the exhibition space. These are environments now under threat, or already lost, due to unsustainable forestry, expanding construction, and climate change –– the direct consequences of human activity.

The exhibition includes kinetic ryas. The movement is created either by the airflow generated by the visitors, which is amplified by the hanging technique, or by recycled electronics attached to the rya. As the series progresses, the movement within the ryas increases, mirroring the return of species and the growing activity in areas where the environment has been restored. Some works in the exhibition can be touched, allowing the experience to be not only visual but also tactile.

I borrow a magnifying loupe from the station to see the forms and details of the lichens more closely. I have looked up regionally endangered lichen species on the laji.fi website and learned to identify them. Yet, while at Gilbbesjávri (Kilpisjärvi), I cannot bring myself to stop for the lichens. My gaze is constantly drawn to the horizon, which stretches from one fell to the next. I no longer understand why I should search for these endangered species, locate them, examine and study them in detail. The vastness and apparent stillness of the landscape make such a deep impression on me that I feel I need a broader perspective.

Photographed on the slope of Sáná, at Šilismalla.

I decide to put the lichen thoughts on hold and head to the fell. To the left before me, lying above the tree line, is Šilismalla (Pikku-Malla), behind it Gihcibákti (Iso-Malla), to the right Jiehkkáš (Jehkas), and beneath me Sáná, whose summit I never attempt to climb. As I lie there, it becomes clear that my sight alone does not tell me the whole truth. I need to be fully present with my entire body. When I look towards Jiehkkáš, it seems as if I could climb there in about half an hour. The distance is short, just over there, but in reality, my body sweats, stumbles, searches for firmer footing, and truly feels the length of the journey. I suddenly realise that I need to perceive my surroundings with my body in a more multisensory way.

Kelley O’Brien from North Carolina is at the residency at the same time as me. From her, I learn about the ancient rock in the Gilbbesjávri area, one of the oldest in the world. Kelley has recorded the stones and their surprisingly rapid vibrations, and as I listen to the recording, my senses blur, it feels less like I am hearing the stones’ vibrations and more like I am feeling them through the headphones. The experience reinforces my need for multisensory perception and a more holistic bodily presence in observation.

Back in Kiekula, the residential building of the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station maintained by the University of Helsinki, on the shore of Gilbbesjávri, I watch the lingering patches of snow around me and the shadows slowly moved by the clouds. With my eyes, I search for movement on the slopes of the fells. Have the jasas, the snow patches, melted after yesterday’s rain? I wonder about my need to see movement and change. I feel the movement around me in my body, and I understand that farther away, in the direction of my gaze, there is movement as well. Movement is everywhere, movement is in everything, in all the nonhuman bodies around me.

In the foreground at KoskiGalleria is the heijastus (reflection) rya, which is part of the Läike pair of works that my collaborator Väinä Räsänen and I created for the Koskifest multimedia art festival, held in Enonkoski in July 2025. Photo: Ida Lindgren.

I graduated from Taidekoulu Maa in 2020 and am currently pursuing further studies at Turku University of Applied Sciences, where I am working on my thesis. In it, I explore and articulate my kinetic rya practice in more detail, and how I understand multispecies collaboration and its connection to craftsmanship-based work. In my kinetic rya practice, I engage in slow working methods, doing things differently, and multispecies collaboration. My works arise from movement-based perception, experiences of non-belonging, and how the tactility of ryas leads to diverse sensory experiences.

Gilbbesjávri gives me a gift, a reminder to return to my body, to the foundation of my practice. My body’s collaboration with other bodies. I, or we, for my body is made up of many; we weave, knot, spin, and dye wool, nettle yarn, and cotton –– that is, bodies that continuously influence one another. Here, it becomes clear to me that movement-based perception is not achieved by eyes or ears alone; my body, as a multisensory being, must be fully involved in this process. After all, I perceive other bodies with my body, which are all part of this assemblage: lichens, fells, water, wind, animals.

Before coming to Gilbbesjávri, I was in residence in Enonkoski, where I wove the heijastus (reflection) rya. The rya is part of the Läike pair of works, which my collaborator Väinä Räsänen and I created for the Koskifest festival. For the first time, I wove outdoors for an extended period and experienced how nonhuman bodies, the wind, rain, and sun, affected both my own body and the bodies of the rya’s materials. How wool fluff becomes heavier in damp weather, nettle yarn breaks more easily, colours fade in the sun, and the wind carries the threads away. My slow practice slowed even further, and I was delighted by it.

The experience of weaving outdoors intertwines with the process of grounding my body at Gilbbesjávri. It becomes something tangible; the words to describe it are still unfinished, yet I strive toward expressing it. I know what is happening more precisely in my body. Collaboration is doing things differently, intuitive and flowing, but not frictionless. I am not alone, but part of a whole. I read and reflect on this together with Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Like Bennett, “I believe it is wrong to deny vitality to nonhuman bodies, forces, and forms” and that it is important to “expose a wider distribution of agency” in which “the common materiality of all that is” is emphasised. The vital materialism presented in the book helps me move toward “a heterogeneous monism of vibrant bodies” and thus assists me in articulating the idea of collaboration among nonhuman bodies. (Bennett 2010, 121-122).

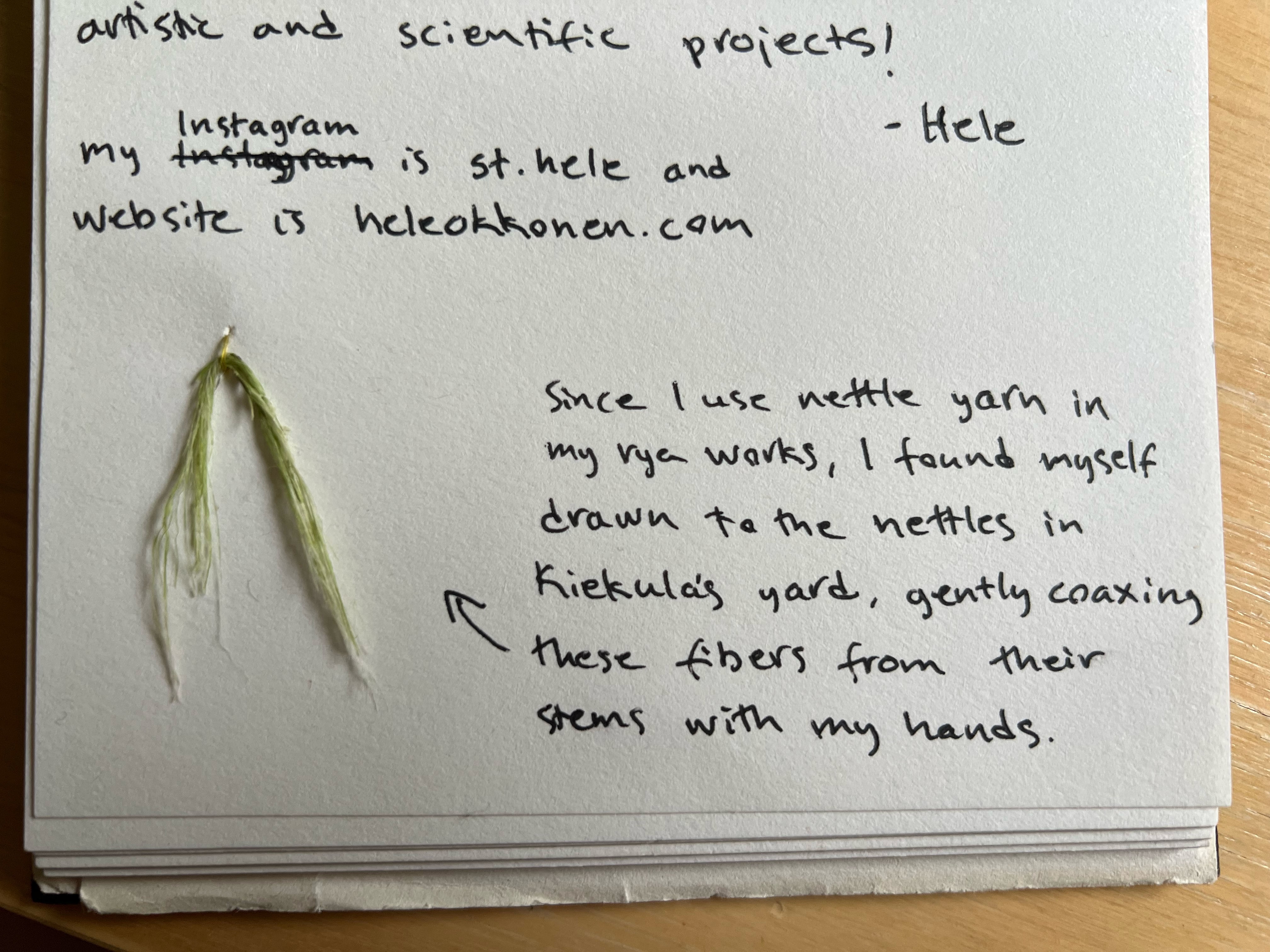

Nettle fiber processed in the yard of Kiekula

The water of Gilbbesjávri is chilly; it pricks and refreshes. I hear from my neighbours that the ice only left two weeks ago, and this year, summer is late, so to speak. I think about the impact of human-driven climate warming on the annual cycle and the weather. On the shore of Kiekula, the researchers’ car gets stuck in the mud, because the snow came so quickly last winter that the ground didn’t have time to freeze properly. My friend, who stays in my room during the first week, and I borrow a rowboat from the station. We set off rowing toward the foot of the Šilismalla slope. The area is a nature reserve, so we don’t land but stay on the surface of Gilbbesjávri’s body. The water rocks us, and I feel the movements in my body. Movement is everywhere.

After spending time at Gilbbesjávri, I understand that the direction of my artistic work is now moving toward an increasingly abstract expression through my kinetic rya practice and nonhuman collaboration. The original intention of the residency — to study locally endangered lichen species — has shifted to a larger scale and toward expressing movement perceived through a more abstract and multisensory bodily observation. The idea is still unfinished, yet significant to me, and I allow it to mature for a while before I begin to address it in my ryas. Therefore, the autumn Siimes – katve II exhibition will not include a kinetic rya inspired by the lichens of the Gilbbesjávri area, but a new direction is underway, and I am pleased about it.

On the last day, I am accompanied by a white reindeer whose shoulder is marked by two black spots, like the inverted colours of the snow patches on the fells. I imagine an eternal symbol forming around them. The reindeer stays in the yard of Kiekula all day, where I separate fibers from the nettle stems and listen to Suvi West’s Syntien kummun naiset, a book I highly recommend.

In the evening, as I take the nettle fiber spindle I made during the day to the station’s notice board with my greetings and return the station’s loan bike, the reindeer ambles up the yard’s uphill path towards me. It feels strange that it stayed all day in the yard where no other reindeer usually came, and as I return to the house to go to sleep, it just leaves the yard. I thank it for the company and am grateful for the time I spent at Gilbbesjávri.

Many thanks to the Bioart Society, Kilpisjärvi Biological Research Station, Kelley O’Brien, Leena Valkeapää, Saija Lehtola, my father, Väinä Räsänen, and Veera Vehmas.

References:

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press. https://www.paradigmtrilogy.com/assets/documents/issue-02/jane-banette--vibrant-matter.pdf